Poorly optimized algorithmic content is frustrating for users, in more ways than one.

Ads (For Items)

It’s a new, somewhat dystopian warning: look for gifts in Incognito Mode so the ads don’t give away what you were looking at. Unfortunately, in a world run by websites that want you to make an account for your purchase, Incognito Mode is less helpful than it used to be.

Websites take notice of what you look at and buy, and then they juggle that into a measure of intent – are you actually planning to buy X item? How many times did you check it, and how long did you look at the listing? Did you look at other listings like it? Did you message the shop owner, or ask a question? Did you ‘heart’ it? If you did, it’s going to recommend more proportionally to how much you interacted with said item. But what about gifts, you may ask? How does the algorithm know I’m not buying this nurse-themed cup and this teacher-themed lanyard for myself?

Turns out any website using Google tools to track engagement knows what data to leave out in the long-term – they’re gathering so much data that it’s not really a loss! Given enough time to read your patterns, they’ll be able to figure out you’re done looking and will squirrel that knowledge away for the Gift Finder stuff (or whatever Google does with all of the data it stores on you) later. That’s… creepy, but not necessarily worsening your experience.

But what About the Ones that Aren’t as Optimized?

What is worsening the user experience is a lack of understanding context by other, less developed and less conscientious algorithms. Google Ads was notorious for following you with an item you looked at once before their target-testing showed users didn’t like it, and it was prone to mistakes anyway; companies following Google as an example didn’t always move on when they figured that out, though. Target sending coupons out for baby carriers and bottles came across as gauche, even when it was right – you hope nothing bad ever happens, but the first trimester for a pregnant woman can be very scary, which is why it’s tradition to hold off until the second trimester to start sharing that info. Imagine a company butting in with a mailed coupon and effectively telling your household that you’re pregnant before you get to!

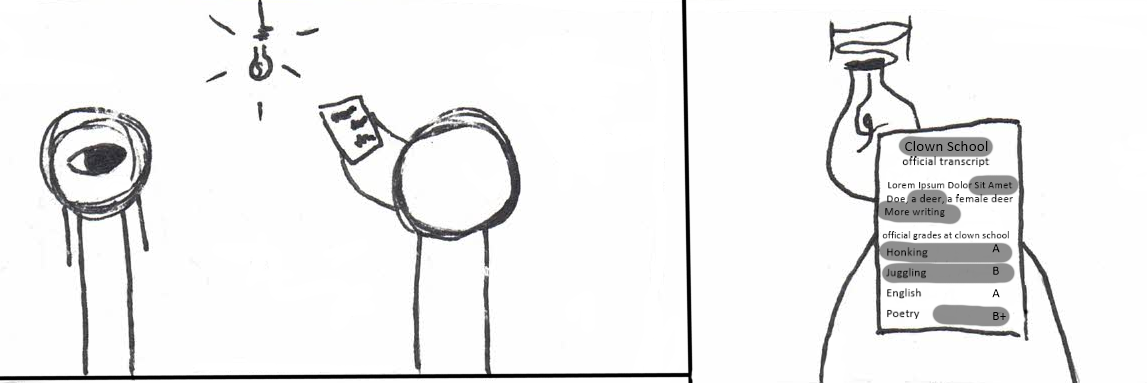

And where ‘haunting’ a user with an item they glanced at is still popular, it can make it tough for users to go back to casual browsing without that item appearing, making a website less appealing to casually visit. For example, Etsy – Etsy does not seem to be able to distinguish between items you’d buy once, like musical instruments or coffee tables, and items you’d buy over and over, like soap and other consumables. As a result, if you buy an instrument off Etsy, you don’t necessarily get ads for items related to that instrument – you just get ads for more Instruments. Take these screenshots of my Etsy front page:

This was immediately after I bought an instrument from the shop OrientalMusic, and if this was candles or snacks or something, showing me more stuff from the same vendor would be reasonable – as it is, I can’t window-shop for stuff Etsy thinks I might like because all it thinks I might like right now are more instruments.

“Shuffle” and Spotify

Spotify allows its users to make playlists of songs, but it also attempts to generate separate playlists for the user. “Discover Daily” and Discover Weekly” are designed to show the user new (or new to them) music that they might like. “Release Radar” aims to get you to new songs from other bands in your playlist. And then there’s the “On Repeat” playlist, which is meant to play you the songs that you’ve heard most often.

The obvious issue with that: if you’re a free listener, Spotify decides which songs you’ve heard most often. If you’re a mobile listener on the free plan, you don’t have the option to not shuffle on the playlists you make, so the algorithm determining what song you’re going to listen to next is also ultimately deciding the On Repeat playlist, not you. The other playlists also learn that you like those same songs more, and Spotify’s algorithms scramble to provide you recommendations based off of the songs you like the most… the songs it thinks you like the most, which aren’t songs in the playlist but are instead songs you listened to, which Spotify decided.

Effectively, Spotify is feeding itself its own data, not yours!

Even worse, the shuffle function isn’t truly random – it’s run on an algorithm too. True randomness would be a saving grace for “On Repeat” – if you have a song in multiple playlists that you listen to often, statistically, it’ll pop up in On Repeat before songs you only have in one. That is, if it were actually random – unfortunately, it’s also decided by an algorithm. If you’re getting the same three or four songs every time you start a playlist, and the same handful the majority of the time afterwards, even with plenty of other songs in the list, that’s not a coincidence.

OneZero says that Spotify divides its functions into exploit and explore, and when it’s trying to exploit, it’s easily tricked into a feedback loop of the same music you hear all the time. Explore is in the same boat, but it uses other people’s data to suggest songs that Listeners of X liked – leading to the same conclusion every time you open the Discover playlist. If you didn’t like those songs last time, it doesn’t care – it’s recommending them again to you now because Listeners of X liked it, and you listened because the algorithm put it first in line in shuffle, which leads to it thinking you like X a lot. Wired.com says that it can get itself so stuck on what it thinks you want that trying to break out and get new recommendations in your Discover playlists is better done on a fresh account. Yikes.

Youtube Recommended

Youtube’s recommended page is usually pretty good at picking up what you’d probably want to watch… as long as it has some history about you first, and also as long as you don’t stray too far from what you normally consume. Countless Youtubers have filmed themselves opening Youtube in an incognito window so they can show how few videos it takes to get into some crazy conspiracy theory videos – turns out the Flat Earth is never more than five or ten clicks away! A phenomenon that some noted was that new accounts who didn’t have any other data would get funneled into a rabbit hole once Youtube had the slightest smidge of data about them – and when conspiracy theory videos have high engagement (i.e lots of comments arguing) and enough run time for ad breaks, they’re considered above average content. Wonder why Youtube is putting those little Context bars below videos with sensitive topics now? That’s because it was forced to reckon with the algorithm’s tendency to feed misinformation to newcomers and people who ‘did their own research’ right into believing the Earth was flat and lizard people were real.

Sources:

https://www.wired.co.uk/article/spotify-feedback-loop-new-music