In 2012, game developers were beginning to experiment with a principle known as “always on”. “Always on” had many potential benefits, but the downsides keep the majority of games from ever attempting it. Many of the notable standouts are games that require team play, like Fall Guys or Overwatch. Others without main-campaign team play tend to fall behind, like Diablo 3 and some of the Assassin’s Creed games. Lag, insecurities, perpetual updating, etc. are all very annoying to the end user, so they’ll only tolerate it where it’s needed, like those team games. It’s hard to say that this hack wouldn’t have happened if Blizzard hadn’t switched to an “always on” system… but some of their users only had Battle.net accounts because of the always-on.

Blizzard’s account system was designed with their larger, team games in mind. It was forwards facing, and internet speeds were getting better by the day. Users were just going to have to put up with it, they thought. Users grumbled about it, but ultimately Blizzard was keeping data in good hands at the time. You wouldn’t expect Battle.net accounts created purely to play Diablo 3 to lose less data than the user profiles in the Equifax breach, right? Blizzard didn’t drop the ball here! What did Blizzard do right to prevent a mass-meltdown?

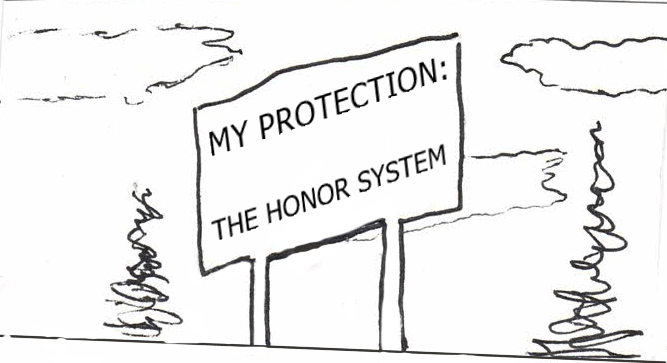

Hacker’s Lament

The long and the short of it was that Blizzard’s stuff had multiple redundancies in place to A) keep hackers out and B) make the info useless even if it did end up in the wrong hands. Millions of people had lost data in similar events before, and security experts were more and more crucial to keeping entertainment data safe. Blizzard was preparing for the worst and hoping for the best, so even when the worst struck here, they were prepared.

The actual hack was defined by Blizzard as ‘illegal access to our internal servers’. It released the listed emails of players (excluding China), the answers to security questions, and other essential identifying information about accounts into the wild. However, due to Blizzard’s long-distance password protocol, the passwords themselves were scrambled so much that the hackers might as well have been starting from scratch. This is still a problem, but it’s not a world-ending, ‘everyone has your credit card’ problem. Changing the password on the account and enabling 2FA was considered enough to shore up security.

Potential Issues

Lost email addresses aren’t as big of a problem as lost passwords, but they can still present an issue. Now that the hacker knows an email address was used on a particular site, it’s possible to perform a dictionary attack, or regular brute forcing! This strategy will eventually work, but the longer and more complicated the password is, the less likely it is to succeed on your account in particular.

A secondary problem is the lost security questions. Those are a form of 2FA. Depending on the question asked, guessing something that works or brute forcing it again is dangerously easy. Sparky, Rover, and Spot are very popular names for American dogs, for example. If the hacker is able to identify that the player’s American, and then guess the name of their first dog, they’re in! They can change the password to keep the legitimate player out. (Part of Blizzard’s response is forcing users to change their security questions for this reason). 2FA that uses email or mobile is generally preferred.

Battle.net acted as an overarching account for all the games, and made the stakes higher for an account breach. All the online Blizzard games went through Battle.net. Losing access could mean losing access to hundreds of hours of game progress. Or worse: credit card data and personal info.

Online, Always, Forever

The event provided ammo for anti-always-on arguments. There was no option to not have a Battle.net account if you wanted to just play Diablo’s latest game. Some users were only vulnerable as a result of the always-online system. If they’d simply been allowed to play it offline, with no special account to maintain that always-online standard, there wouldn’t have been anything to hack! Previous Blizzard games didn’t require Battle.net. People who stopped at Diablo 2 seem to have gotten off scot-free during the hack. This is annoying to many users who only wanted to play Diablo 3. They might not find value in anything else about the Battle.net system. Why bother making users go through all this work to be less secure?

When discussing always online, there’s good arguments to be made for both sides. Generally, always on is better for the company, where offline gaming is better for the consumer. Always on helps prevent pirating, and it gives live data. Companies need data on bugs or player drop-off times, which can help them plan their resources better and organize fixes without disrupting the player experience.

On the other hand, consumers with poor internet are left out, as lag and bugs caused by poor connection destroy their gaming experience. As games move more and more to pure digital, buying a ‘used game’ only gets more difficult for the consumer. Companies treat purchased games as a ticket to a destination, rather than an object the consumer buys. Games used to be objects, where anybody could play the game on the disc even though save data stayed on the console. Buying access to Diablo 3 via Battle.net means that there’s no way to share that access without also allowing other people to access the Battle.net account, which stores the save data. It’s the equivalent of sharing the console, not just the disc.

Handling

The response to the stolen, scrambled passwords was for Blizzard to force-reset player passwords and security questions, just in case the hackers somehow managed to unscramble them.

2FA is always a good idea, and Blizzard strongly recommended it too. 2FA will do a better job of alerting you than the default email warning ‘your password has been changed’ will after the fact. After you’ve received that email, the hacker is already in. Depending on when you noticed, they could have already harvested all the data and rare skins they wanted by the time you get your support ticket filed! Setting up 2FA first means that you’re notified before that happens.

All in all, Blizzard handled this particular incident well! Companies are required to inform their users about potential online breaches, but some companies do this with less tact than others. Formally issuing an apology for the breach isn’t part of their legal requirements, for example. What made this response possible in the first place was Blizzard’s competent security team, alongside a set of policies that were strictly followed. Logs and audits in the system ensured that Blizzard knew who accessed what and when, which is critical when forming a response. Blizzard was able to determine the extent of the problem and act on it quickly, the ultimate goal of any IT response.

Sources:

https://us.battle.net/support/en/article/12060

https://us.battle.net/support/en/article/9852

https://comsecglobal.com/blizzards-gaming-server-has-been-hacked/

https://medium.com/@fyde/when-too-much-access-leads-to-data-breaches-and-risks-2e575288e774