Experts have struggled with this problem for decades. How do you measure something subjective, and how do you do it in a consistent way? How do you, a researcher, discover pain points and weak spots in your process for the customer? Carefully crafted questions with non-leading answers are difficult to make, though, so…

Here’s how to make a bad one.

1) Make the question leading.

“How positively do you see Our Company”, “Do you think of Our Company in a positive light?” And “What is your opinion, on a scale of 1 to 5, of Our Company?” Are all going to get the company wildly different results. Using adjectives to describe the product or service to lead the customer into the ‘right’ answer is hardly new, but it’s always been a bad idea! Genuinely happy customers don’t need your survey questions to rail-road them into the right answer. Unhappy customers will be frustrated that they can’t make their opinion known. The data on the back end will suffer as a result.

Leading questions that express negative sentiments towards competitors and non-buyers are also likely to cause problems. “How unhappy were you with your previous company?” reads like a red flag – they might have switched for any number of reasons, and now they’re being forced to read these questions defensively. When someone breaks up with their partner, you don’t bad mouth the ex unless they start doing it first!

2) Don’t include any negative options.

If you don’t include a null option, you’re gonna get bad data. Picture a question asking you if you’ve heard of a handful of platforms, and think positively of them, and it assumes you’ve heard of at least one – that is, it doesn’t give you an option for ‘none of the above’.

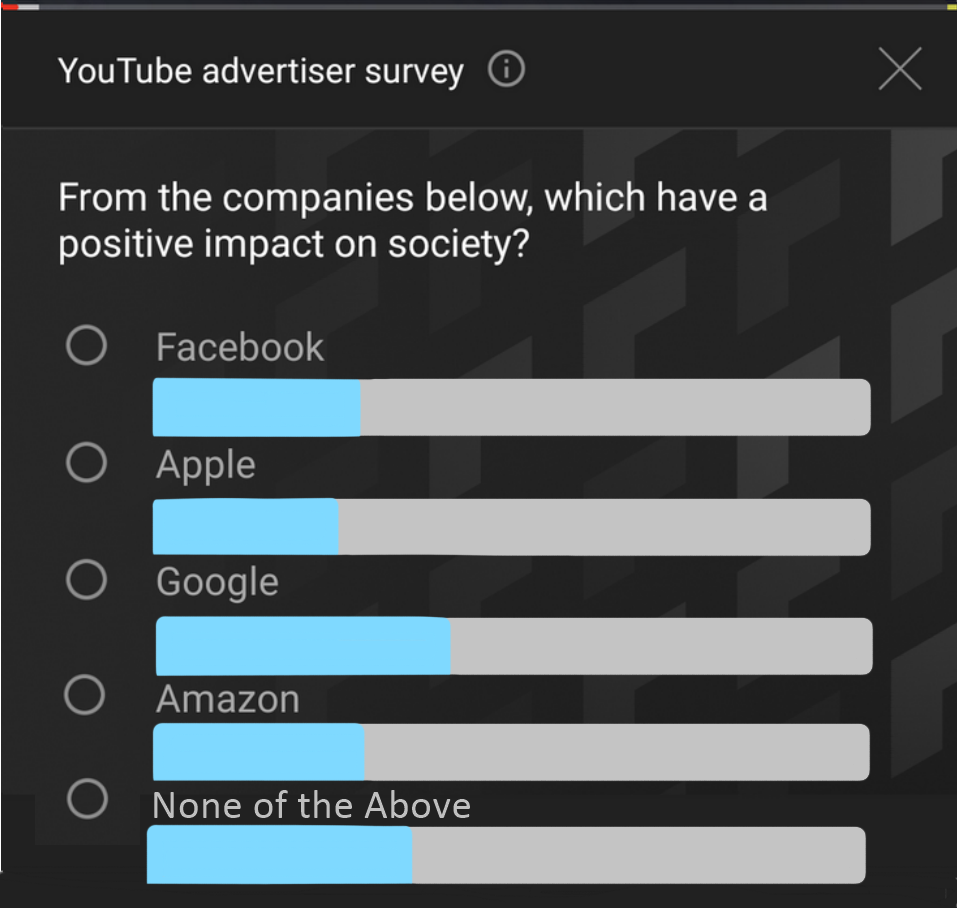

This ad is a perfect example of what not to do! In a world with so much access to information, big companies are under the gun like never before. Between Google’s quiet removal of “Don’t Be Evil” from its mission statement, Apple’s use of child labor, Amazon’s poor working conditions, and Facebook’s data harvesting, none of these companies are particularly guilt-free. They’ve done bad things. Bad things that have a negative impact on the world. Their positive impacts are directly tied into the things that make them bad. There’s no ‘right’ answer where one is ‘good’ and the rest are ‘bad’. The survey takers either select a company they haven’t heard bad news from lately, pick an answer they’re not happy with, or don’t select a company at all and move on without answering. None of the answers fit! Well-informed consumers are effectively excluded from the survey! Without a ‘none of the above’, a percent of potential surveyees can’t answer the question honestly.

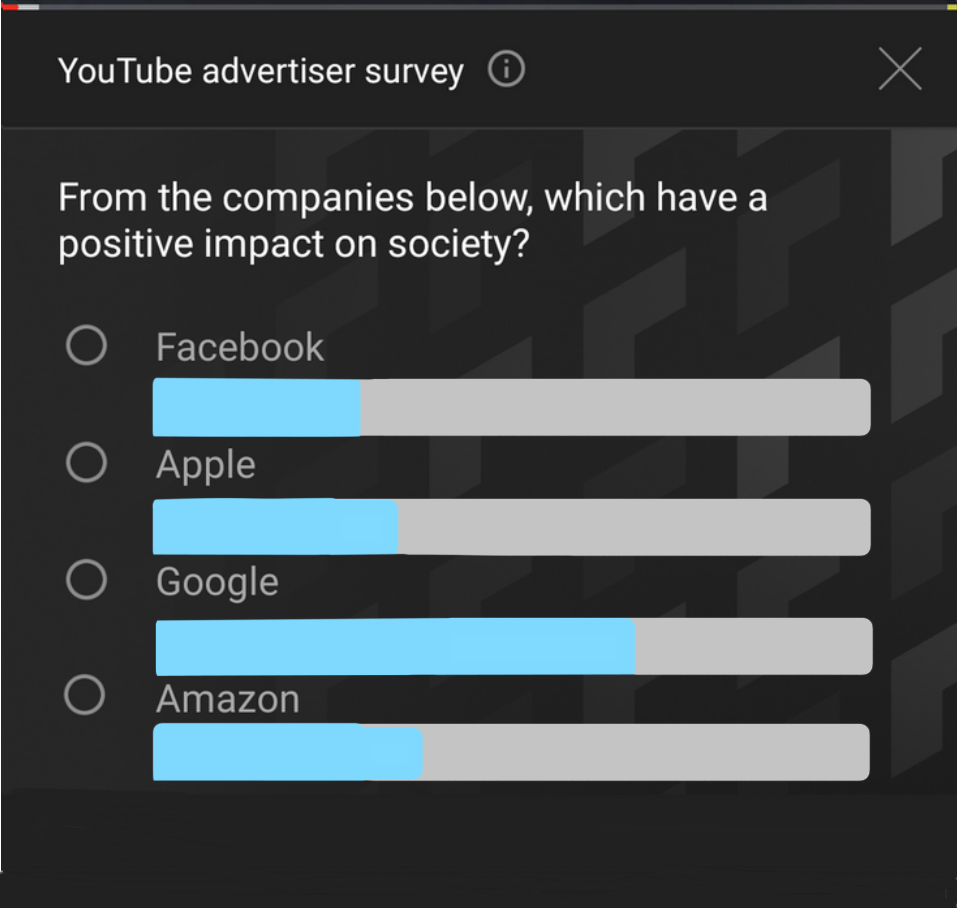

While the initial results may hypothetically look like this:

The actual results could hypothetically be closer to this:

But the company has no way of knowing that ~25% of their customers, hypothetically, don’t like any of these options without a null option! Getting real numbers is critical for questions like these. Beating around the bush with “You must like one of them, right?” is only harming the companies themselves by giving them an inflated image of their public perception. People know they did bad things, this leading question isn’t going to make them forget that.

3) Only make the survey available after completing an action.

Asking users to sign up for your newsletter before granting them access to the survey will not only weed out the dispassionate users, it will also greatly annoy users who really want to leave constructive feedback!

Studies show that even getting customers to the survey (even if it’s digital!) is a great undertaking, usually reserved for people who are moderately happy or upset. When companies put barriers like newsletter signups in front of their users, they’re not getting willing sign-ups, they’re getting worse, more polarized results. Only very happy or very angry people are committed enough to sign up for the newsletter, and the inconvenience of having to do so may make both survey-takers slightly more negative in their answers. The people who were going to leave a 4/5 stars and a blank comment box are gone. That’s not a good thing. Instead of reinforcing valuable data, you’ve skewed your answers towards outliers!

If you really want users to sign up, include it as an option at the end of the form. Don’t force it – the engagement won’t be worth the irritation inflicted on the customer.

4) Make your questions incredibly long and/or confusing.

Starting any 1-5 question with “Are you Aware of…?” “Do you…?” or “Have you considered…?” is just a bad time. Those are yes/no, survey-takers are going to be confused. Not every option is scalable! Poor wording can also make otherwise simple questions with simple responses a confusing word puzzle.

“Do you agree that contrary to popular belief, the general public should put sand into lakes and rivers?“

“Did our employees not do a good job?” “Was your ad experience intolerable?” “Do you agree that the job could or could not have been done better?”

None of these work with simple yes/no, and now the survey maker has to elaborate in the answers with a “yes, they should…” or “no, I didn’t…” which is more work than making the question straightforward.

On top of poor wording, making questions too long or too short for the customer to parse is a surefire way to confuse even the best readers! If you want bad results, make sentences go on forever when they don’t need to.

4) Let People Self-Select – and Then Call it Representative of the Whole

Former President Donald Trump was famous for running approval polls via newsletters and his favored conservative website ads. Obviously, people who don’t like him are not going to want to sign up for his newsletter or watch these forums, so they never saw these polls. People who did like him were more likely to be signed up to conservative sites and newsletters, and as a result, the survey results skewed massively conservative, and positive in his direction. People self-selected into news sources that he could exploit. In this way, he could claim that he was very positively viewed by the general public, when really the survey barely reached anyone outside the bubble. Yeah, sure, technically the survey was available on public websites… that doesn’t mean the public saw them. This is a public page, I could slap something together really quick and call it a survey, does that mean I ran a public survey with valid results? No.

The questions were also incredibly leading, designed to reinforce support for Trump and his political party instead of acting as questions, but we covered that in Question 1. No matter what you think of him, this is an objectively bad method for discovering data.

By citing these poorly-ran surveys, he was able to convince some that the media really was depicting him unfairly. After all, how could he have gotten an 80% approval rate out of his own survey when the media says he’s only at 30%? The answer: his organization picked outlets that loved him and called it an accurate representation of the real world, while the Gallup poll sampled randomly. Speaking of which…

5) Don’t Sample Randomly

It’s possible to avoid people self-selecting into your survey… and yet, you might still get a skewed answer out of them. It’s a lot of hard work to extract data from customers in a meaningful way. Random sampling is crucial!

If you want weird or minimal results, do something that keeps distinct portions of the population from answering. Make it difficult for customers on mobile to fill out the survey, and you’ll cut an enormous amount of potential participants out. Allow customer service agents to point out the end-of-experience survey only to the happy customers, and only get happy results. Pick certain zipcodes and ignore others for political polling, which will give any organization the answers it wants. Kick participants for having the ‘wrong’ results so you only get right ones.

Manage that, and you haven’t randomly sampled anything!

5.5) Give access to non-customers

Sometimes, however, you do need to sample within a population to get results for that population. I don’t own anything Apple-branded. If Apple were to survey me now about owning a product, I would clutter up their results with noise. And yet, Apple sometimes asks me what my opinion of their brand is in online adverts, without asking first if I’m ever going to buy an Apple product. I don’t care about Apple. My answer is noise. And yet, if I answer without maliciously picking 1s for everything, they won’t know that! They won’t dismiss me as an outlier. It’s okay to put a gate in front of the survey if it filters out noise and bogus survey responses.

6) Torture the data you do get

JD Powell’s company came into being when he watched his coworkers massage data over and over to tell their higher-ups what they wanted to hear: “Customers Are Happy and you’re doing a Great Job ™”. Of course, this didn’t reflect the reality of the situation, and the company continued to suffer from quality issues that could have been solved sooner if they’d listened. Why run a survey if you’re not actually looking for results? Why let customers think their voice is heard, only to cut some of them out for being a little too disagreeable? Outside survey companies exist because internal departments can’t show their managers the real, raw data – they shoot the messenger, and then wonder why profits are down if surveys are so good.

Every company wants to hear that customers are very happy. Every company wants that. Some companies want it so bad that they refuse to accept news of anything else. If you want to do a bad job, torture your data! You’ll have no idea what customers are actually thinking!

7) Ask everything, all at once

This is a bad idea. Interactive ad-surveys are supposed to be short and sweet. Ask too many questions and the customer may bail before they complete the survey. However, tracking one specific variable is for good surveys, and we’re not doing that. Do a bad job and ask every question, all at once. Get yourself three surveys worth of data.

One of the hardest parts of designing a survey is getting juuust enough information to build out your data. Jeep owners might be more likely to fish, that’s valuable data. How important is it to know if they own Apple products, when choosing what materials to make seat covers with? Will knowing the customer’s favorite TV show help your company determine what scent to make their detergent?

Data overload is really cool for finding weird correlations in things, but when the researcher has to present something with meaning to their higher-ups, it’s very easy to get lost in the sauce. A fifty-question survey is also far too intense for an ad, or for a post-shopping survey on a receipt, so that limits the pool to people signing up for surveys voluntarily instead of the hit-n-run kind found in ads.

http://neoinsight.com/blog/2017/02/21/on-the-trumppence-media-survey-dark-patterns-ux-and-ethics/

Hyperlink for Formatting: Survicate.com

https://blog.marketo.com/2017/01/4-effective-methods-to-increase-your-survey-response-rates.html