The phrasing of a ‘no thanks’ in dialogue boxes can be a real turn-off for potential customers.

Website newsletters, coupons, and other assorted pop-up boxes may ask you to sign up – and if you don’t, you click to decline the offer. Is it possible to word it in a way that changes the minds of customers?

I Don’t Want to Subscribe

In some businesses in Japan, employees are expected to gauge the response to an idea they had purely by tone. “Sure!”, “Sure.”, And “Sure… but it will be very hard.” are the only options, and ultimately, they are still all affirmatives – if the other person wanted to step on toes, they would make “sure…” sound like “sure!” and forge ahead, and they would have plausible deniability while doing it. Foreign business associates consulting with Japanese companies were sometimes a blessing because they lacked this context – they’d charge right in with a “no”. This took a lot of social pressure off of the middle managers who knew issues existed, had tried to bring them up before, but went ignored because of social rules stating they must minimize things, or phrase them in a way that isn’t unpleasant.

Being forced to say “I don’t like this” or “I don’t want that” is often uncomfortable, so many cultures have rules for how to say no. While not as extreme as Japan, even people in the U.S. would find it rude to just respond with “no”. This is why websites often say something like “No thanks” instead of just “No” or an X in the first place!

It’s not rude, but it is short. As web design advanced, more and more websites began including the context; instead of a simple “no thanks”, they’d say “No thanks, I don’t want to sign up”. The decline then sounds human without being overly presumptuous, and it became the new standard.

More importantly, while these longer versions sound more human than simply saying ‘no’, it’s also reminding the more impatient users of what the box is for. Even if they didn’t read the pop up, they read the decline option before they clicked it. They know a newsletter or coupon is available now. This is a tried-and-true method. It’s neutral, professional, and clear.

Forced To Lie

Website designers strongly recommend simply stating facts when writing out the line, instead of trying to make the user feel guilty for clicking ‘no’.“No Thanks, I don’t want your newsletter”, or “No Thanks, I don’t want to stay up to date on X” are certainly easy to guess if that user declined to sign up for the service. These are statements of fact.

But not everyone follows expert advice! Where websites put themselves in danger territory is when they try to get sassy, or smarmy with their decline option. Websites, for seemingly no reason, will imply that their users are stupid, and have ugly clothes, and that they must enjoy staying that way if they don’t agree with whatever the box is pushing. If someone in a real, physical store told you that when you declined to sign up for email coupons, you’d probably leave a negative review!

They’ll tell users that they must hate fun, or want to live in their own little world:

Or more. There’s more, and a ton are worse. Barely anybody likes this. And yet websites still try it so often that there’s a term for it: Clickshaming! There’s a hashtag on Twitter, there’s a subreddit on Reddit, and there are tons of websites showcasing the worst of the worst when it comes to clickshaming.

Emotional Response

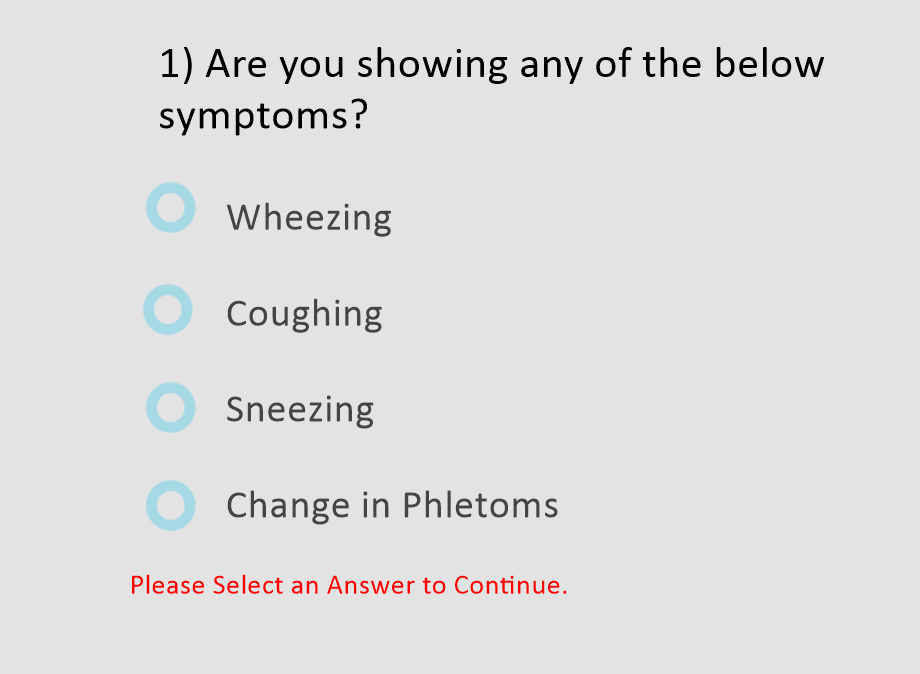

The theory is that by inciting emotion, they’ll catch people who are on the fence.

Tell the customer a joke, make them laugh, and they’ll like you more. Act busy in front of a customer and they’ll feel pressured to decide faster. Link up with good causes, and the client will feel better buying from your store, because they’ll be supporting those good causes indirectly. Emotions are very heavily tied into sales, and the feelings a customer has before, during, and after the pitch determines whether or not they actually go through with it.

When a website says “We’ll hate to see you go!” They’re trying to pull an emotional response, so that you’re more likely to come back. A good website designer tries to make the website feel good and comfortable to use. The problem is that “haha, you’re not leaving without spending money, right?” is only a joke if the salesperson can tell that their potential buyer finds that funny, and even then they have to deliver it right, or else it sounds desperate. Sarcasm during a sale is a delicate thing. A human could tell when it would be appropriate to deliver that line to other humans. Putting “Aw, you hate saving money?” in the bottom corner of a dialogue box doesn’t carry that joking tone, and so it comes off really aggressively.

Even giving them the benefit of the doubt, reminding customers that your product can be expensive (and they could save money) isn’t exactly the brilliant strategy it seems on the surface. As mentioned above, the option to leave the dialogue box is sometimes the only option the user is even looking at – those people want to get back to scrolling. Imagine having to click ‘I hate saving money’ so you can look at things you’re not even sure you want to buy yet. If they don’t leave out of spite, suddenly the website is on an uphill battle to sell something to this specific user, who’s been primed to think about saving money.

Emotional response is not a guaranteed hit, especially when the emotion is negative. Clickshaming is a bad idea!

Sources:

http://www.ediplomat.com/np/cultural_etiquette/ce_jp.htm

https://www.klaviyo.com/blog/email-pop-up-tips